This site is part of the project River Logistics, Plantation Imaginaries, Common Winds: The Dockyard Dispositive .

It is drawn from notes for itinerant script for sites related to the Deptford Dockyard and how we might think about it at this important moment of contestation. In it we study the Dockyard from its current conjuncture, drawing in histories that explain the importance to communities of the present. The route is drawn from archival research, conversations with local activists, historians and memory keepers. It is a work in progress. It you have something to dispute or contribute please let us know.

This text is in development.

St Nicolas Church was built in the 12th century and rebuilt in the 17th century. It was known as the ‘Westminster Abbey of the Navy’, St. Nicolas being the patron saint of sailors.

John Wesley, a prominent preacher, in the the 1730s spoke to congregations of 2000 or more, blessing ships as they embarked on the missions of empire. Roughly 3,000 of the voyages that departed from the Thames between the 17th and 19th centuries were for the purpose of kidnapping, imprisoning, and enslaving people from Africa for sale in America and the West Indies. These voyages were called ‘Adventures’ and the prominent among the ‘adventurers’ was Deptford resident and Treasurer of the Navy, John Hawkins.

The following account of Hawkins is drawn from Joan Anim-Addo’s The Longest Journey

John Hawkins, who lived the Treasurer’s House of Deptford Dockyard, could be considered the ‘English father of the Slave Trade’. On his first slaving ship in 1562 he was able to combine trading activities for two chief commodities of the period. He took gold from Lower Guinea and at least 300 slaves from upper Guinea, nearly 1000 miles away.

He had the ‘backing of his father in law - Treasurer of the Admiralty and several London merchants. …Hispanola was his trading stop in the Caribbean and her returned to England in August 1563 with ships laden with pearls, ginger, sugar and hides..

His success laid the groundwork for future trips to Benin and the Niger Delta, which became known as the ‘River of Slaves’

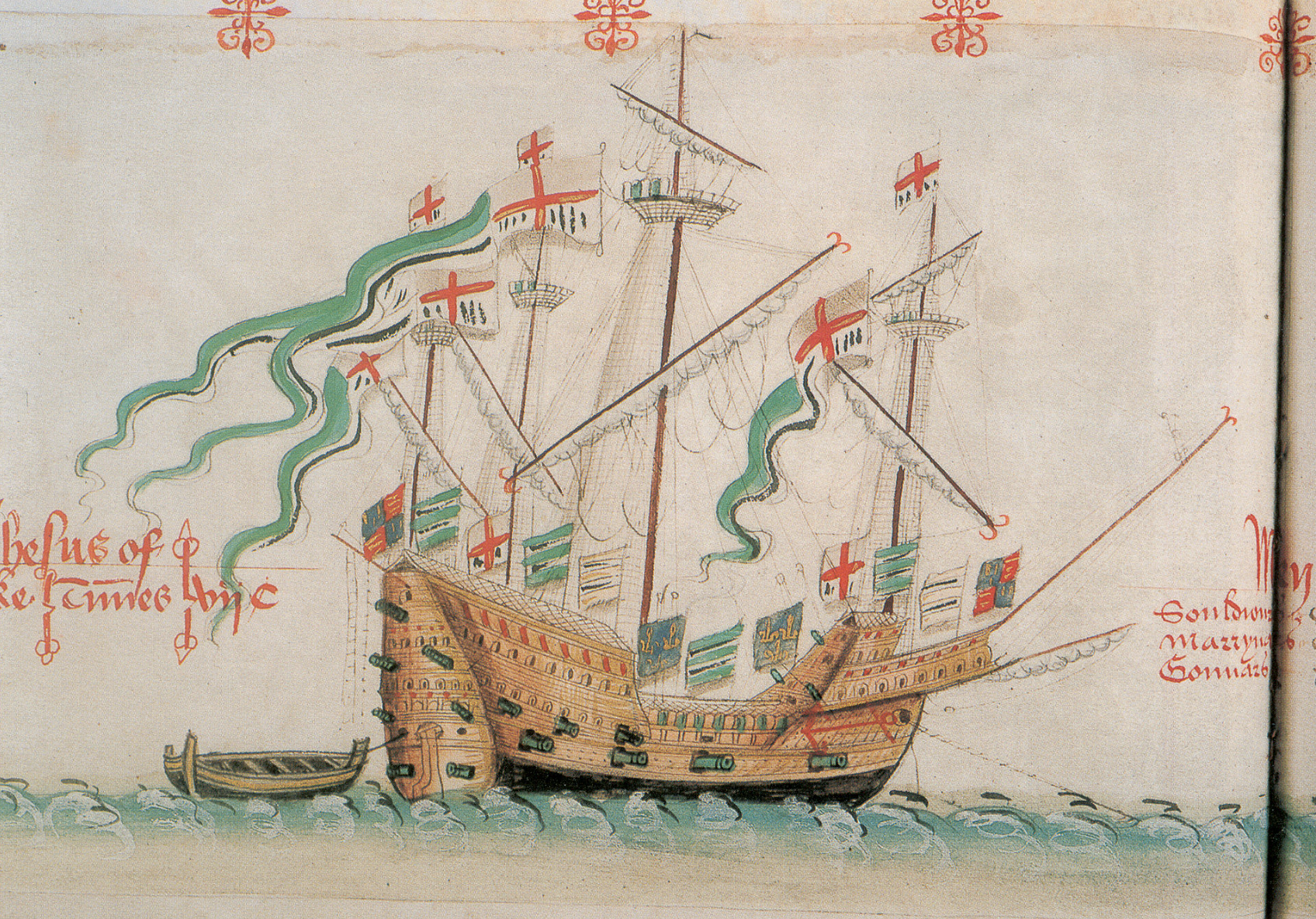

….Impressed by Hawkins’ first expedition Queenn Elizabeth I supported his next through the loa of the Jesus of Lubeck, a 700 tonne vessel purchased by King Henry VIII for the navy. Ships of such size were rarely use for slaving. However such a vessel would prove worthwhile as a boast of English power..

On his third slave hunting voyage in 1567 Hawkins was accompanied by Francis Drake and the Queen’s investment rose to two ships. Often seen as a footnote in the beginnings of slave-trade, Drake was in fact responsible for the violent capturing of thousands of Africans. He and Jonn Hawkins worked together on three separate slaving voyages. Documents in the British Library tell stories of Drake's own acts of rape and brutality. Drake came to St Nicolas each time he left on a voyage.

Also in St Nicolas Church are the very few traces of African people who came, in the 17th century as domestic workers, enslaved people or seaman working on ships. They are recorded only in their deaths.

More is known about their lives in the records of the West Indies, where, from almost the beginning of the plantation system, African people rebelled. Those who were free, who worked on ships, or marooned, passed information word of mouth to share the news of acts of resistance.

Julius Scott calls these acts of ‘masterlessness’ in which unfree people exercise their freedom

‘On the eve of the Caribbean revolution, most English, French and Spanish planters and traders in the region rode the crest of a long wave of prosperity. Nevertheless, they continued to grope much as they had at the end of the last century, for common solutions to the problem of controlling runaways, deserters, and vagabonds in the region. As long s the masterless men and women found way to move about and evade authorities, they reasonsed, these people embodied submerged trasditions of popular resistance which could burst into the open at any time. Examining the rich world which these mobile fugitives inhabited - the complex (and largely invisible) underground which the ‘mariners, renegades and castaways’ of the Caribbean created to protect themselves in the face of planter consolidation- is crucial to understanding how news, ideas and social excitement travelled…